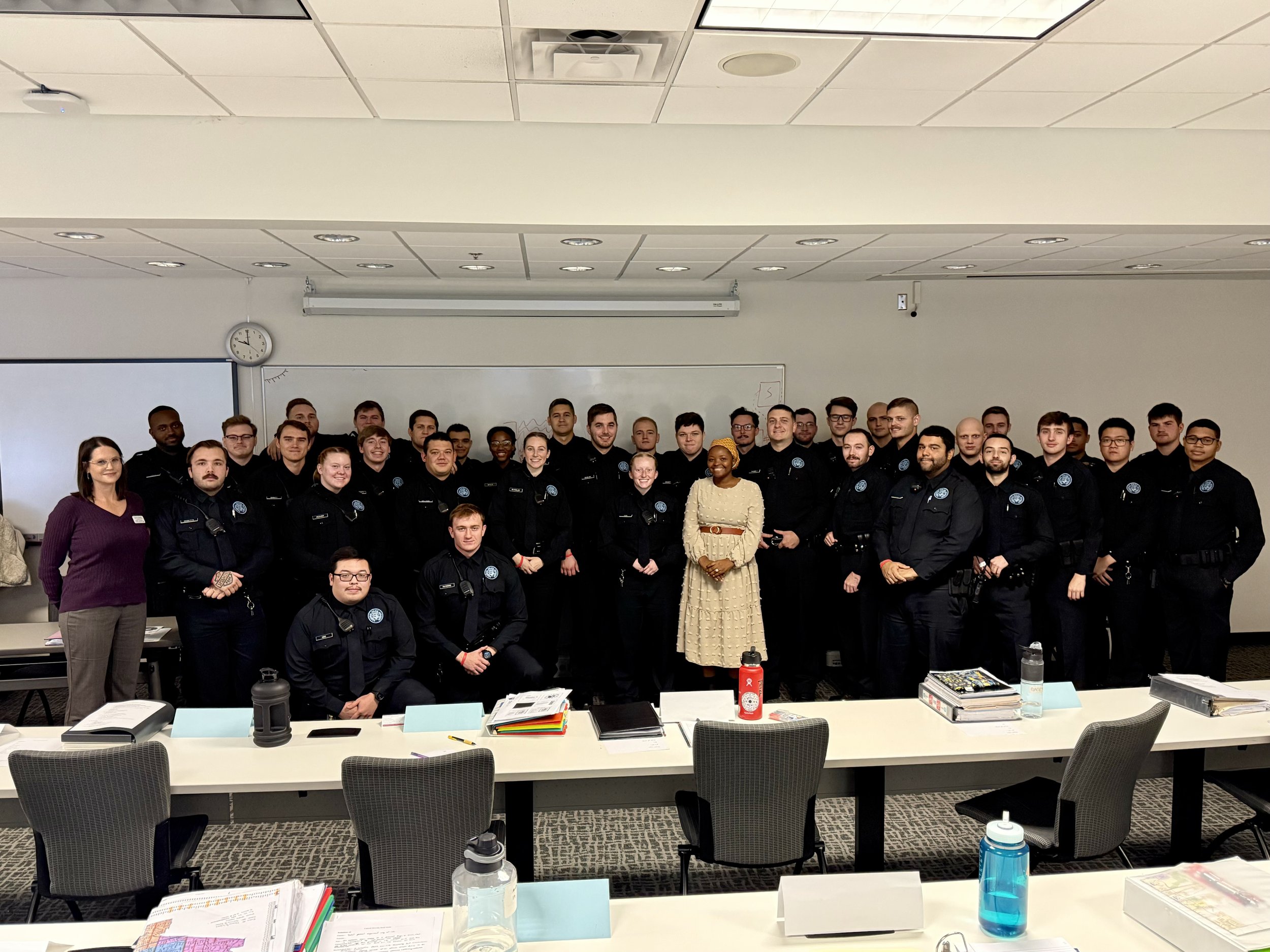

Della Lamb Trains KCPD on Refugees and Cultural Differences

By Sophia Donis

“Nadine, think back to when you were a little girl living in a refugee camp. Under what circumstances would your dad call the police for help?” Claire Koehn, Health and Wellness Manager at Della Lamb asked.

“Maybe if there was a dead body,” Nibimenya Nadine Pasikari, Wellness and Outreach Coordinator at Della Lamb said.

Shared during a focus group in 2023, Pasikari’s perspective shocked all the Americans in the room and sparked a larger conversation about how cultures around the world view the role of law enforcement. Rose Brooks, a domestic violence center in Kansas City and a frequent partner of Della Lamb, hosted the focus group to learn more about refugee experiences.

The stories and knowledge shared that day made such an impact that Rose Brooks reached out to the Kansas City Regional Police Academy, creating an opportunity for Della Lamb to educate academy recruits about refugees.

Since their initial presentation in the summer of 2023, Della Lamb has presented to the Kansas City Regional Police Academy many times, teaching recruits about the journey of refugees, cultural differences, and best practices for serving newcomer communities.

“We have to bridge that gap,” Koehn said. “The resettlement agencies are the refugee experts in their communities, and their communities need to remember that we exist and that we can lean on each other.”

Gaining a New Perspective

Photo courtesy of Della Lamb

Officer Oasha White, Instructor at the Kansas City Regional Police Academy, said she was not sure what to expect when inviting Della Lamb to present during her Minority Relations Class. After the presentation had such a positive response, however, she made it a permanent part of the curriculum.

The presentations start with the foundational knowledge of who a refugee is and why they have been forced to flee their home. Then, recruits are walked through various scenarios and invited to step into the shoes of a refugee to better understand their journeys.

Recruits are asked to imagine being forced to leave Kansas City due to a war and ending up alone in a country where they do not speak the same language. After a group discussion, recruits then try to decipher Pashto and Arabic sentences on a sheet of paper.

“I do that for them to understand when you are under pressure, or when you are stopped by the police, even if you speak a little bit of English, you forget everything and do not know what to do,” Pasikari said.

Understanding Cultural Differences

Pasikari’s presentations heavily focus on cultural differences in other parts of the world that might result in unique experiences when serving refugee communities. One notable example she offers is that in many cultures, it is commonplace for someone to get down on their knees and profusely apologize when they have done something wrong.

“The louder they are crying and begging for mercy, the more it seems sincere to them in their culture,” Pasikari said. “But it is freaking out the police officer who is in front of them.”

She explains that refugees are taught when they first arrive in Kansas City to not jump out of the car if they get pulled over by the police. However, refugees often have the immediate instinct to get out of the car so they can get on their knees and beg for forgiveness before receiving a ticket.

From the law enforcement perspective, White said this cultural difference is important for recruits to understand so they know what is happening when they pull someone over.

“They learn that just because there are inconsistencies in interactions, does not mean someone is trying to cause harm and there could be a cultural reason this is happening,” White said.

Pasikari also teaches recruits about different cultural meanings for eye contact and why someone getting pulled over would avoid making direct eye contact.

“In many cultures, you do not ever look anyone in the eye because once you look them in the eye, it is a sign of disrespect,” she said. “That means you are not humbling yourself before them and that can be very dangerous if a police officer stops someone, and they do not know why that person keeps looking down.”

Both Koehn and Pasikari agree that if both refugees and law enforcement are not properly trained on what to do in these various scenarios, a traffic stop is not going to go smoothly.

Building Trust with Clients

Photo courtesy of Della Lamb

If a refugee has a negative experience with law enforcement, Koehn believes word will spread in their community and people will not call the police if they need help.

“That individual is going to back to their community leader and their community and tell every single person what happened,” she said.

To help build trust between refugee communities and law enforcement, Koehn recommends improving lines of communication between community leaders and police officers. Community leaders are trusted to guide closeknit refugee communities and are often the first to hear about many issues. If they have a point of contact at the police department, they can bring issues to officers directly and begin building solid relationships.

One of Koehn’s long-term goals with this outreach initiative is to continue strengthening Della Lamb’s relationship with the Kansas City Police Department. Eventually, she hopes KCPD officers will lead law enforcement cultural orientation classes so clients can begin to understand the police are there to help and they can call 911 if they need to.

“Our refugees are going to be interacting with police officers at some point in their life in the United States,” Koehn said. “We do not want that first interaction to be one of fear or doubt.”